By Felix Carpenter

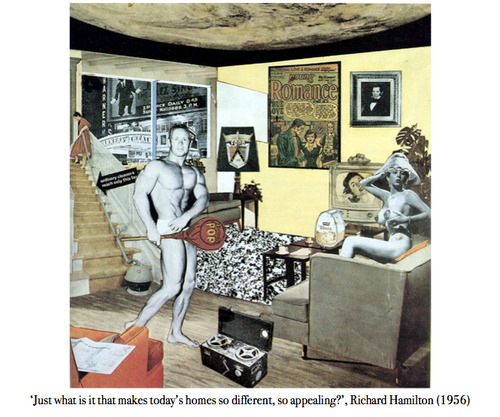

1956, British artist Richard Hamilton produces an artwork representing modern society. His collage, created from magazine cut-outs, “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” was revolutionary. Portraying an idealised perception of the American dream home, featuring the latest mod cons and the grotesque ‘perfect’ couple, a bodybuilder and a glamour model, it became instantly iconic, and later recognised as the first work in the ‘Pop Art’ style.

Hamilton was the first to synthesise post-war mass-consumption culture into a single image, and at that one roughly only ten inches squared in size. I was fortunate enough to visit the recent Hamilton exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, and was instantly struck by the irony of the tiny artwork with its huge and testosterone fuelled and silicone filled subjects. In a consumer society where bigger is better, this remains a smart juxtaposition.

Pop culture is a form of collective consciousness, a mixture of images, phrases and ideals that permeate societies throughout the world. What Hamilton’s artwork shows is a snapshot of pop culture at one particular place and time.

When we admire the American society of the 1950s and 1960s, we are looking back at the period through Hamilton’s distorted spectacles. The image we have of the period, characterised by the work of artists such as Hamilton, as well as Andy Warhol with his Campbell’s Soup Cans, and Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book paintings, is optimistic, bright and clean. But what was it about homes then that made them so different to ours, and so much more appealing?

In short, because our demands are higher. Comparing the approach of more recent artworks offers a powerful insight why. Tracey Emin’s proudly unmade “My Bed” or the graffiti art of Banksy, tackle the ideals of society in a very different way to artists fifty years earlier. Condemnation of cultural institutions is no longer in the form of ironic admiration as with Hamilton, it is spelled out explicitly, placing pop culture itself under attack.

This phenomenon is not limited to elite artists though. Even in ordinary conversation, whatever the topic is concerning, focus soon becomes thrust upon negative societal issues such as inequality, sexism and racism. Often this is reasonable, these are of course important and pervasive issues, but occasionally it is fairly random or arbitrary – becoming a new, social justice orientated version of Godwin’s Law (the positive probabilistic correlation between length of a conversation and a comparison involving Nazism being made), which inevitably ends up proving correct in itself as well.

Having an overtly critical cultural mindset is partly a result of having things too good for too long. For many people in the UK, the daily drudgery of #firstworldproblems is too common. The notion that having all the latest mod cons is an aspiration is gone, it has become par for the course. Ideological decadence has overtaken ambition. Sometimes, and this is used as a vague catch-all, it is difficult to see how you would change your life for the better, even if you could. Recently I heard a tellingly accurate aphorism from a friend, “Happiness is so fauxcore, unhappiness is normcore now.” While all this is based on generalisation, perpetual satisfaction without real gratification is probably the ultimate ‘first world problem’, and leads to a questioning of our fundamental cultural ideals.

Simultaneously, pop culture is expanding beyond, even if it is still dominated by, the ‘West’. People are consuming more ideas than ever, and for new and different reasons, all in a world that is demographically larger than ever and reacting to an age of relatively new-found hyper-connectivity. Pop culture is gradually becoming broader in scope and more culturally diverse, and the tone of how we think about the world slowly changing in the process. It is difficult to deny that the ideas of ‘sustainability’ or ‘feminism’ are a part of pop culture across the globe, even in places where these ideas may have little practical currency.

Today popular culture is a global language and not just for art galleries. The growth and development of popular culture should be celebrated and revered as one the great of achievements of humanity, and we should try our best to regain some of Hamilton’s ironic optimism, appreciating the many positive aspects that pop culture and society have to offer; ‘look how good things are, but we can still do better.’